Among the hundreds of popular songs written for Broadway shows and vaudeville acts in America with themes relating to the Middle East there is a sub-genre that relates the adventures of Jewish girls (mostly from New York City) with sheiks, sultans and pashas. In these songs they travel far across the sea or at least to the nearest vaudeville house where they can sing of their exploits. The songs recount the adventures of solitary women who are lost in the industrial urban setting, working for pitiful wages and who long to be the center of attention and power in a faraway land. The Orient served as the primary locus of these dreams, whether the Far East or the Near East was intended; from the standpoint of Americans, China, Japan, India and Araby were part of a continuum of exotic lands that blended together to exude a heady perfume of romance. With the conclusion of the Spanish-American War the Pacific islands, Hawaii and the Philippines became part of this consciousness, but they never had the enduring appeal of the Orient. Aladdin, Ali Baba and Sinbad were joined with Cleopatra and Salome to form the main cast of characters for plays, pantomimes, dramas, operas and, of course, popular songs.

There were many reasons for the attraction of this group of songs. They were topical, reflecting the events of the day in international affairs, something that an immigrant population would follow with interest especially when the events involved their homelands. The crumbling fortunes of the Ottoman Empire affected sections of Eastern Europe as well as the Middle East, so there was an abundance of material from which to draw. The lyrics of these songs generally juxtaposed the heroine and some powerful male, with no doubt left as to the winner of the contest. Above all, these songs afforded an opportunity to satirize the contrasts in culture between America and the Orient and a rich set of stereotypes were created to accomplish this end.

This sub-genre must also be set in the context of women entering the workforce in the late 19th century. Immigrant Jewish girls were only a part of the available pool of factory workers landing on American shores.

The Melting Pot of Immigration That Was New York

In 1906 the New York Sunday World carried a headline that the city was welcoming “Twelve New Citizens a Minute,” a calculation made on the basis of the number of immigrants flooding through Ellis Island that year. A century later it is difficult to imagine how the American economy could absorb such crowds until one remembers the geometric expansion of the number of industrial plants in the late nineteenth century and the raw manpower needed to run those mills. Construction work then was also highly labor-intensive, absent the machinery that we take for granted today. Block and tackle riggings lifted the stone and brick on building sites and animal power hauled the wagons of supplies around the cities. Teams of bricklayers, hod-carriers, masons, riggers and workers of all sorts were needed to raise the monuments of American industry and progress.

One example of how this process worked can be seen in the case of the Botany Worsted Mills in New Jersey. The factory owners from Passaic and Paterson would send agents to Ellis Island to meet the boats coming in from Europe to scout for potential workers. The new immigrants would be brought back to the mills, introduced to their fellow-countrymen already working on the line and integrated into the “American way of life” within the week, surrounded by people who spoke their language and understood their sense of dislocation from the home country. Assistance in finding housing and some basic social services could also be provided by earlier immigrants who had achieved a toe-hold in American society. Sometimes ideas from the “old country” would be introduced in the new, such as food cooperatives that would offer members lower prices for necessary foodstuffs. These co-ops could also insure that special food imports from Europe not normally stocked in American markets would be available, another vital link with former lives.

The ideal of a “melting pot” was never really realized by these immigrants. The various groups remained culturally separate and were blatantly stereotyped as a way of re-enforcing their identities in a new environment. During the 1920s in one New England woolen mill, for example, the spools and bobbins would fly across the factory floor as the Finns had periodic floor fights with both the Red and the White Russian immigrants, a reflection of the revolution occurring in post-war Russia. Americanization was still an imperfect ideal.

A good example of this un-homogenous attitude appears in a song from the 1890s that highlighted the variety of women working at the Botany Worsted Mills. The company had originated in Germany, but in order to avoid American trade tariffs the owners had established a branch in America, enabling them to use a “Made in America” label on their products. The owners also discovered that they could greatly increase their production by hiring women, not just men, to work the looms. The women and girls, it was noted, “while at the outset had no knowledge of mill work, [they] soon acquired great skill, equal to that of the best trained [male] hands.” The women also attracted the attention of the men in the mills by the dresses they wore (which were varieties of their national costume until such time as they could afford new American fashions). They became known as the Botany Mills Girls, whose notoriety was captured in a song with words set to a popular tune. The references to the women’s nationalities are a virtual catalogue of the stereotypes of the day.

THE BOTANY MILL GIRLS

(ca. 1890)

Tune: “He Never Cares to Wander” by Felix McGlennon

This world is made up of all sorts, each one thinks he is best,

We often judge our neighbors by the style in which they’re dressed.

Society belles in Central Park, parade in gorgeous style,

But see our Botany Mill parade, I’ll bet it makes you smile.

CHORUS:

I always like to ramble by the Botany Mills,

To see the fresh arrivals as they come,

They’re as happy as can be, in the country rich and free,

They never think of “home, sweet home.”

You will find the “Lady of Lyons” there, and the “Maid of Athens,” too,

The Bohemian girl, gypsy maid and the “dark girl dressed in blue,”

And Cinderellas by the score with their hob-nailed number nines–

Hungarians, Poles and Russians, Jews of a hundred different kinds.

See the German girl with head erect, she walks with queenly grace,

And there’s a petite French damsel with a round, sweet, smiling face.

The Jewess, too, with dark, bright eye and plump, well-rounded form,

If the Jewish race was cursed, I think the curse has done no harm.

Now hustle, boys, don’t lose your time, look round and choose thy schatz,

She will soon save your money, you’ll soon be buying lots.

The Scheeny is a dandy, at saving there’s none such,

And still I don’t know if she beats the money-grabbing Dutch.

This musical catalog of the various types of women in the mill was typical of the ethnic humor and the stereotypes of the period. Music hall and vaudeville house acts capitalized on the different groups, German, Irish, Jewish and Italian, to name a few, that would be in any typical audience in New York. Performers–in order to survive in the business–quickly caught on to the ethnic composition of the house at any given performance and tailored their acts accordingly. Some acts solved the nationality (and linguistic) problem by using no language at all: these were the jugglers, acrobats, dancers and the like. Singers would have a repertoire of Irish, Yiddish, German and Italian songs to be arranged to suit the demands of the audience.

Vaudeville had another attraction for many immigrants, namely as a way to get out of the factories and make some “real” money as a performer. Just how this worked can be easily understood by looking at the experiences of Fanny Brice. Brice could make $10 in prize money singing in a saloon-theatre in New York for one evening. This compared to the weekly salary of a couple of dollars for a 60-hour work week earned by seamstresses in the Garment District sweat shops. Her brother would stand behind the back curtain and scoop up the coins thrown on stage during her numbers, netting them another $5. If one had the ambition and the talent, clearly the stage was the road to prosperity.

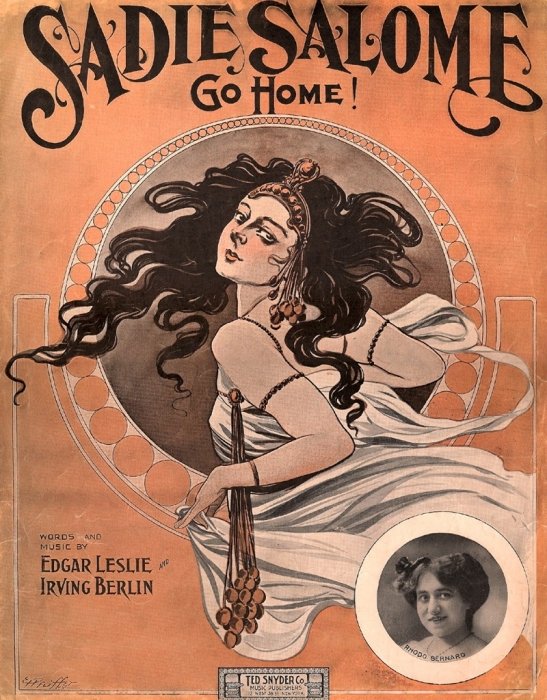

The Salome Rage: Sadie Cohen learns to do the oriental dance

The American premiere of Richard Strauss’ Salomé at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1907 was the scene of outrage among the social set and a rich source of parody material for the vaudeville houses and carnival shows of Coney Island. Salome’s dance and the climactic moment when she raises the head of John the Baptist from its platter and kisses its lips set off a storm of outrage in the audience. J. P. Morgan successfully blocked any repeat performance of the opera as long as he was on the board of the Met, a ban that lasted until 1934. The “Dance of the Seven Veils” could not help but inspire burlesque performances, not only because of the subject matter of the dance itself, but also because of an tradition in the opera production that called for a more nubile substitute for the diva to perform the dance. In short order six and seven “Salomes” were competing at any one time in Coney Island for the attention of the folks along the Boardwalk in the years immediately following the opera’s premiere in New York.

While the majority of the performers concentrated on the strip tease aspect of the act, a variation emerged in the ethnic theatres, namely the Jewish girl who wants to be part of the theatrical craze and do her own version of Salome. After all, the original Salome in the New Testament was a Jewish girl.

Fanny Brice had some success in talent nights in the city, but when she was asked to perform at a club on Long Island, she needed a new song for the act. Irving Berlin had one that capitalized on the Salome craze by setting it in a Yiddish context; Sadie performs as Salome against the wishes of her sweetheart Moses. In the lyrics note that “op’ra glasses” rhymes with “dresses.” Brice insisted that her wriggling during the song (“Who put in your back such funny motions?”) had little to do with her attempt at an oriental dance and more to her attempts to stay comfortable in a starched sailor suit that kept catching her “you know where.”

SADIE SALOME GO HOME (click here for details)

SADIE SALOME GO HOME (click here for details)

w. and m.: Irving Berlin

©1908 Ted Snyder

Sadie Cohen left her happy home

To become an actress lady,

On the stage she soon became the rage.

As the only real Salomy baby,

When she came to town, her sweetheart Mose

Brought for her around a pretty rose;

But he got an awful fright

When his Sadie came to sight.

He stood up and yelled with all his might:

CHORUS:

Don’t do that dance, I tell you Sadie,

That’s not a bus’ness for a lady!

‘Most everybody knows

That I’m your loving Mose,

Oy, Oy, Oy, Oy, Where is your clothes?

You better go and get your dresses,

Everyone’s got the op’ra glasses.

Oy! such a sad disgrace, No one looks in your face;

Sadie Salome, go home.

From the crowd Moses yelled out loud,

“Who put in your head such notions?

You look sweet but jiggle with your feet.

Who put in your back such funny motions?

As a singer you was always fine!

Sing to me, ‘Because the world is mine!’

Then the crowd began to roar,

Sadie did a new encore,

Mose got mad and yelled at her once more:

The Ottoman Empire and the Sultan: Rebecca Goes to Mecca

Aside from the biblical associations with the Middle East that Salome supplied, on the world stage at the beginning of the 20th century the tottering remnants of the Ottoman Empire, “the sick man of Europe” was in all the news. The Turks still controlled the Middle East, from the Balkans and Anatolia through the Levant to Iraq and parts of the Arabian Peninsula. The mythological Turk was even more powerful in western imagination: the warrior of the East wearing a great turban and brandishing a scimitar storming the gates of Vienna. The great palaces of Istanbul with their harems were the embodiment of exotic locations. Turkish baths had been memorialized in Orientalist paintings and drawings replete with naked women in various languid poses.

Descriptions of life and intrigue in the inner rooms of the palaces and the baths had been written by a band of intrepid European women who penetrated the harem rooms and experienced the rituals and delights of the Turkish bath. Among them were the wives of British diplomats assigned to the Sublime Porte who had the time and an inquisitive nature that led them to discover what life was like behind the harem walls.

The Americanized version of this exploration did not rely on the wives of diplomats, however, but on the solitary, intrepid Jewish woman. Why Jewish? The first reason is that the origin of some of these songs was the Jewish theatre in New York. Here people in the audience may have come from parts of Eastern Europe still under Turkish control and so would have personal memories of the Turks. A second reason was that only a woman could tell the stories in these songs; a man could never gain access to the places of most interest, the harem and the baths. And finally, the women narrators were from among the immigrants who had traveled across the Atlantic at least once and who might be believed when they recounted their imaginary adventures in the Middle East.

One universally known locale in the Middle East was Mecca. As the focus of the annual Islamic pilgrimage, the location had entered the English language as a synonym for the goal of one’s desires: Stratford-upon-Avon had become the Mecca for American pilgrims, said the London Times in 1887 [21 Oct., 9/1]. The actual location of Mecca in the modern Saudi Arabia was lost in the general association of the city within the Turkish Empire and its dislocation became common in songs about the Middle East. For Rebecca, a girl from New York, a trip to Mecca took her to Turkey, not Arabia, but her adventure had little to do with religion or serious culture in any event. As in “Sadie Salome” the Yiddish pronunciation is built into the lyrics: “Mecca” rhymes with “tobecca,” a reference to the growing acceptance of women smoking cigarettes in America, although clearly a “foreign” practice. Her attire is now reduced to a Turkish towel and she insists on calling her brother “Mohammad instead of Moe.” The ultimate success of the trip, however, can be seen in her achieving nothing less than the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

REBECCA CAME BACK FROM MECCA (click here for details)

REBECCA CAME BACK FROM MECCA (click here for details)

w. & m. Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby

©1921 Waterson, Berlin and Snyder Co.

Across the way from where I live,

There lives a girl and her name is Rebecca,

She’s twenty-three.

She saw an oriental show

And then decided she would go To Mecca,

across the sea.

And so she went one day,

To Turkey far away,

And she lived near the Sultan’s den;

She stayed there just two years,

Got full of new ideas,

And now she’s back home again.

CHORUS:

Since Rebecca came back from Mecca,

All day long she keeps on smoking Turkish tobecca;

With her veil upon her face,

She keeps dancing ’round the place,

And yesterday her father found her

With a Turkish towel around her,

Oh! Oh! Ev’ryone’s worried so;

They think she’s crazy in the dome;

She’s as bold as Theda Bara,

Theda’s bare but Becky’s barer.

Since Rebecca came back home

In Mecca where the nights are hot,

Rebecca got and awful lot of learning,

She certainly did.

She goes to sleep when shadows creep

And has to keep a bowl of incense burning,

Some classy kid!

Her mother feels so sad,

Her brother Moe is mad,

And he keeps on complaining so,

To satisfy her whim,

she keeps on calling him

“Mohammed” instead of Moe.

CHORUS:

Since Rebecca came back from Mecca,

All day long she keeps on smoking Turkish tobecca.

She lays on a Turkish rug,

Ev’ryone says she’s a bug,

And since she’s back home from the Harem,

She has clothes but she don’t wear ’em.

Oh! Oh! Ev’ryone’s worried so;

She made the Sultan lose his throne;

Once her little sister Sonia

Wore her clothes and got pneumonia,

Since Rebecca came back home.

Sophie the Cigarette Girl Takes Egypt by Storm

Sophie worked in a cigarette factory in New York until she found a more lucrative line of work as a dancer in Egypt. Oriental dancing as parodied in vaudeville did not require years of practice like the ballet; all one had to do was twist and twirl in the right costume. Sophie, like her stage sister Ella, goes to Egypt to perfect her talent. She returns in triumph to be a vaudeville star at the Palace Theatre in New York, billed as “Queen Borealis.” Even though her costume consists of fourteen yards of veiling and a diamond necklace, she is immediately recognized by the “hicks from Fact’ry Six” as their old friend Sophie.

SHE GYPPED EGYPT (click here for details)

(On The Nile)

w. & m. Sam Marley & Billy Heagney

©1922 M. Witmark & Sons

In a big Tobacco Factory-ee,

Sophie’s work was not satisfactory-ee,

For instead of rolling Trophies

All the time was spent of Sophie’s

At the Dance Egyptian you will see-ee,

Each Oriental twist

She could simply not resist,

So one fine day she sailed away

And I’m here to whisper this,

CHORUS:

She “Gypped” ev’rybody down in Egypt,

When she landed there she had

those natives beat a mile, for style.

When she did the simplest movement,

It showed improvement of those on the Nile, while

They paid heavy dough whenever she played

Ev’ry time she wiggled

All the Bohunks wore a smile

Poor Sophie’s hand for the coin was itchin’

She took ’em all like Grant took Richmond,

She “Gypped” Egypt on the Nile.

From the land of Pyramids she’s sailing,

And a lot of postal cards she’s mailing,

Her name’s now Queen Borealis,

She’ll play three weeks at the Palace

With her maids and fourteen yards of veiling,

Press agents will declare,

“She is right from Over There,”

But all the hicks from Fact’ry Six,

Who worked with her declare:

She “Gypped” ev’rybody down in Egypt,

By the pyramid she claimed relation to the Spinx, that minx,

Her stage door was lined with princes,

She won those quinces with her naughty winks-ginks!

Their gifts piled higher than the sand drifts,

Sophie wore a string of Di’monds and a roguish smile,

They never knew the she learned that f[l]irty

Dance from an East Side hurdy gurdy,

She “Gypped” Egypt on the Nile.

Now in her Stutz as she rolls ’round gaily,

She thinks of butts that she once rolled daily,

She “Gypped” Egypt on the Nile.

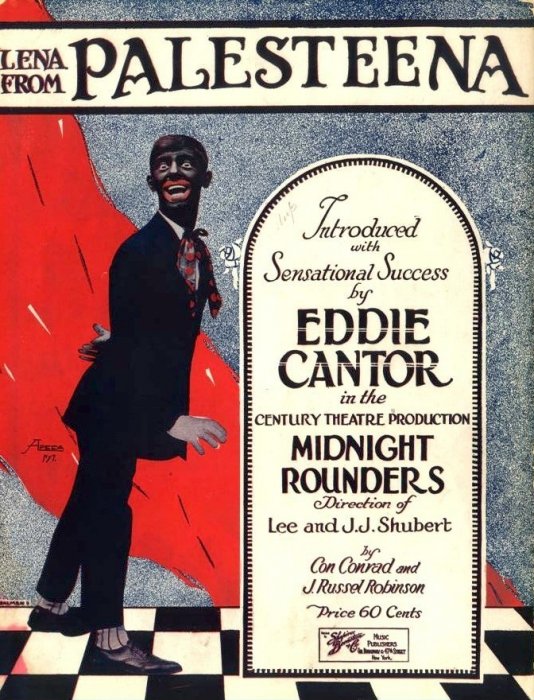

Lena and her concertina become the latest hit in Palestine

The establishment of the British Mandate in Palestine after World War I opened the ancient land of Israel to modern Jewish emigration. The growth of Zionist organizations in America popularized the idea of returning to Eretz Yisrael, but not everyone was interested in making this commitment in the face of success and growing prosperity in the United States. The attraction of returning to the land, however, remained part of the Zionist program and could be made more entertaining when couched in terms of one woman with more limited prospects in New York who might find Palestine the perfect place for her talents.

Stereotypes abound in these lyrics. Lena is fat, hence undesirable in New York, but acceptable in Middle East. “They like ’em plenty that way out there” as is said of Egyptian Ella, another saftig expatriate (see below). The music she makes sounds awful to American ears but is a hit in the Middle East where their “music” sounds to Americans like cats howling. Palestine is a desert country where camels roam across the sand, where Arabs live in tents. When the Arab women imitate Lena’s style of dress, the result is absolute nonsense (“some wear oatmeal, some farina”), but the over-riding concern is to find a word that rhymes with “Lena,” never mind the sense.

PALESTEENA / LENA FROM PALESTEENA (click here for details)

PALESTEENA / LENA FROM PALESTEENA (click here for details)

w. & m. Con Conrad and J. Russell Robinson

©1920, renewed 1947, Shapiro Bernstein

In the Bronx of New York City Lives a girl, she’s not so pretty,

Lena is her name;

Such a clever girl is Lena, How she plays a concertina,

Really it’s a shame;

She’s such a good musician, She got a swell position

To go across the sea to entertain,

And so they shipped poor Lena

‘Way out to Palesteena,

But now I hear that she don’t look the same:

They say that

CHORUS:

Lena is the Queen O’ Palesteena,

Just because they like her concertina,

She plays it day and night,

She plays with all her might,

She never gets it right,

But how they love it, want more of it;

I heard her play, once or twice,

Oh! murder! still it was nice;

She was fat but she got leaner

Pushing on her concertina,

Down old Palesteena Way.

Lena’s girl friend Arabella Let her meet an Arab fella,

She thought he was grand,

On a camel’s back a-swayin’ You could hear Miss Lena playin’

O’er the desert sand;

She didn’t play such new ones, For all she knew were blue ones,

Still Yousoff sat and listened by his tent,

And as he tried to kiss her She heard that Arab whisper,

“Oh! Lena, how I love your instrument.”

They say that

CHORUS:

Lena is the Queen O’ Palesteena,

Just because they like her concertina,

Each movement of her wrist,

Just makes them shake and twist,

They simply can’t resist,

Her music funny gets the money;

There’s nottin’ sounds like it should,

So rotten it’s really good;

All the girls there dress like Lena,

Some wear oatmeal, some farina,

Down old Palesteena Way.

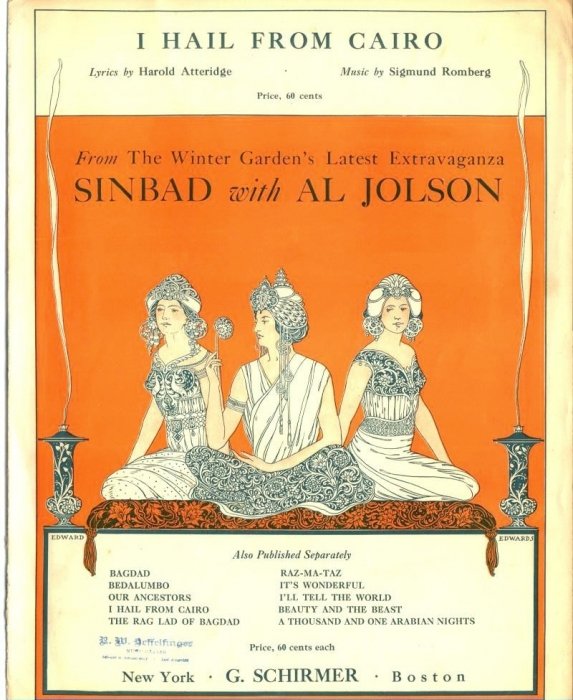

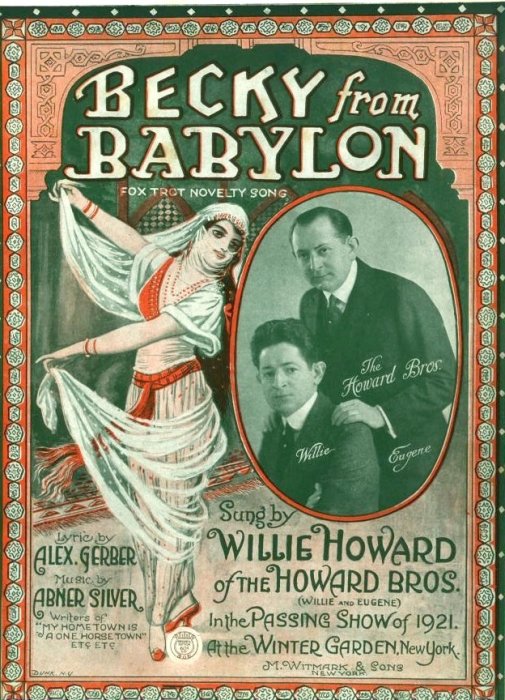

Oriental “Wannabes”

A second category of Jewish adventuress was the “Oriental Wannabe,” someone who was caught in a poor-paying job in America, possibly a second-generation citizen born in America, yet familiar with the legends of the exotic east and imagining what life would be like if only she could get away. The best she can hope for is to have an oriental home address that will impress while at the same time deceive her suitors. The first unnamed adventuress started in Illinois, came to New York to dance in an oriental show and embellished her resumé accordingly. The second, Becky, nee Bifkowitz, claimed to be from Babylon, only to admit that it was the town on Long Island outside New York, not the ancient capital on the Euphrates. Her stage name was nothing as impressive as “Queen Borealis,” but the more recognizable Princess “Oy-Vey-Is-Meer.”

I HAIL FROM CAIRO (click here for details)

I HAIL FROM CAIRO (click here for details)

w. Harold Atteridge

m. Sigmund Romberg

©1918 G. Schirmer

In an Oriental setting in a Winter Garden show

Was a slave girl, very pretty in the colored lanterns’ glow;

Tom-toms beating to her dancing made her seem a vision rare,

Never back in Egypt’s hist’ry did they see such legs so bare.

With this caravan a trader came along with Chorus men,

Saw the Oriental dancer, fell in love with her right then.

“Tell me thy name, oh wondrous maiden!

Say from whence you come, oh do!”

Then the Oriental slave said, “You know where I’m from,”

I hail from

CHORUS:

Cairo, the land of joy,

I hail from Cairo, in Illinois;

I was a slave in the Oriental Cafe,

Selling cigarettes to trav’ling salesmen ev’ry day.

(Oh Schinasi, oh Mogul, oh Murad)

Back there in Cairo, you’ll see the sphinx,

On ev’ry face of those rural ginks,

And by the Great Egyptian Deities,

I got these Oriental knees

In Cairo, Cairo, Illinois.

BECKY FROM BABYLON (click here for details)

BECKY FROM BABYLON (click here for details)

w. Alex Gerber; m. Abner Silver

©1920 M. Witmark & Sons

Down at an oriental show

I saw a dancer there;

Her name was Princess “Oy-vay-is-meer”

And she was from the east somewhere.

When she removed all of her veils,

I recognized her face,

This Hindoo lady was a Yiddish baby

And she came from a certain place–

She was

CHORUS:

Becky from Babylon

(I know her mother, I know her brother)

Becky from Babylon

(She’s got it over Madame Pavlowa)

She learned her oriental ways

As a waitress lifting trays,

She got her famous pose

From washing mother’s clothes.

Becky, she fools with snakes

(Oh what a twister, you can’t resist her)

She’s full of tricks and fakes, Oh,

She’s no daughter of the Pyramids,

Her right name is Becky Bifkowitz,

Ev’ry one thinks

That she is a Sphinx,

But she’s Becky from Babylon (Long Island).

I knew this oriental queen

When Becky was her name;

I knew her when she wore plenty clothes

And when dishwashing was her game.

Now’s she’s disguised from head to toes,

Dressed up in veils of youth,

The other quinces take her for a Princess,

But if they only knew the truth!

She was

CHORUS:

Becky from Babylon

(Oh what a terror, Like Theda Bara)

Becky from Babylon

(She’s full of motion, Just like the ocean)

Cold show’r baths she used to take,

That’s how she first learned to shake,

She dances on her [all] fours,

She learned it scrubbing floors,

Becky, no clothes she needs,

She’s all dressed up in beads.

Oh, What a figure

It would make you dizzy,

She’s got lines, but the lines are always busy,

All the wise ginks

Think she is the Sphinx,

But she’s Becky from Babylon.

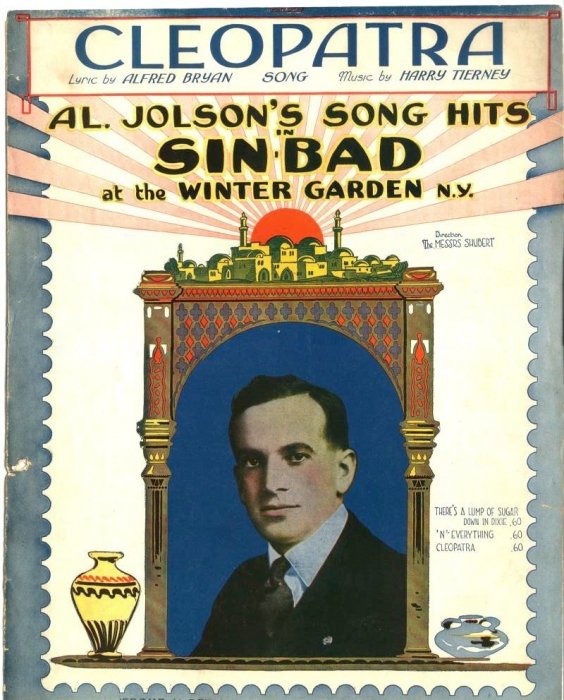

As assimilation into mainstream American life became more common for the immigrant populations, a kind of anti-assimilation awareness also appeared. The use of hyphenated affiliations such as Italian-American, German-American, and later African-American would be incorporated into organizational names. The rise of genealogical societies devoted to specific nationalities and lineages started the investigations into family history by people from all walks of life, not just the “upper crust.” Given the ethnic mixture among the song-writers and audiences, it was inevitable that this probing of family roots should be carried to a comical extreme with certain well-known historical figures such as Cleopatra. Like Salome, Cleopatra had immediate name recognition with any audience, but the song could tell a story about the famous queen that few had ever heard before. Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, was also a child of mixed heritages, Egyptian, certainly, but also Jewish, Hawaiian and a dash of Irish, too! The spread of her family tree and the contributions of each branch become all too evident in her behavior.

CLEOPATRA (click here for details)

CLEOPATRA (click here for details)

w. Alfred Bryan; m. Harry Tierney

©1917 Jerome H. Remick & Co.

You’ve heard of Cleopatra who lived down beside the Nile,

She made a “Mark” of Anthony and won him with her smile.

They say she was Egyptian, but I’ve reason to construe

She was Jewish and Hawaiian with a dash of Irish, too.

CHORUS:

When she stroll’d with bold Mark Anthony on Egypt’s yellow sands,

You could see that she was Jewish by the motion of her hands.

She would shake her hands and shoulders off,

That’s the way she made her “muscle tough”—

I think she was Hawaiian from Honolulu too,

She would dance like this to the Yaka hoola, hicky doo-la, Yaka hoola, hicky doo.

Her mother’s name was Cleo and her father’s name was Pat,

So they called her Cleopatra, Now what do you think of that?

She had a thousand lovers in the true Egyptian style,

When she grew sick of one she threw him to the crocodile,

They say she died heart-broken after many sad regrets,

I really think she died from smoking Milo Cigarettes.

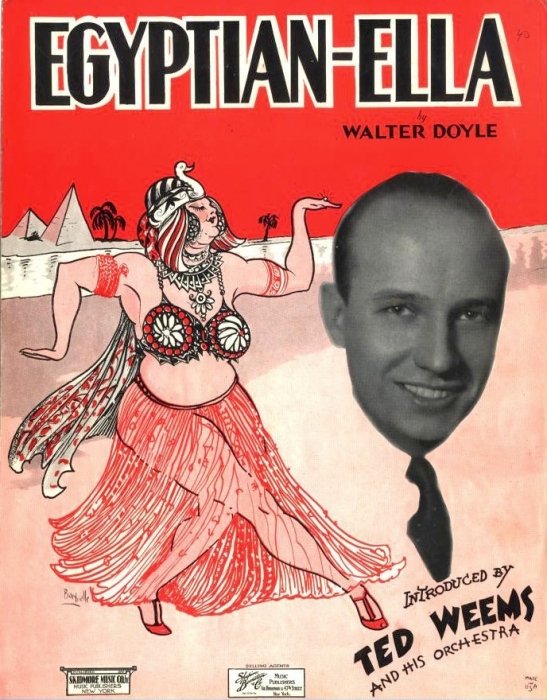

“Egyptian Ella:” saftig becomes a selling point

A century and more ago the perfect image of womanhood was not that of the current leptosomatic configuration. “Pleasingly plump” was not considered a negative compliment, but even then there were limits to the ideal of saftigkeit. Ella had to find that out the hard way, by losing both her job as a dancer and her boy friend due to her increasing avoirdupois. The solution to her problem could be found in the East, where, it was asserted, the men liked women with ample proportions. So the legend of Egyptian Ella was created, the girl who made it big in Egypt by being big. Ella is never referred to as being Jewish, which may reflect the change that was occurring in American life, the assimilation of European Jews into mainstream America. Unlike Cleopatra, Ella does not need a fake genealogy; her talent can speak for itself.

EGYPTIAN ELLA (click here for details)

EGYPTIAN ELLA (click here for details)

w. & m. Walter Doyle

©1931 Skidmore Music Co, Inc.; renewed 1958

Ella was a dancing girl who started getting fat

Ev’ry day brought two more pounds to Ella

Till one day she found she’d lost her job because of that,

Then, to make it worse, she lost her “fella.

And so she sailed to Egypt to forget

But she made such a hit that’s she’s there yet:

CHORUS:

If you hear of a gal who can shake and quake

Till it makes you think of a nervous snake,

They’re speakin’ of EGYPTIAN ELLA

She weighs two-twenty but they don’t care,

They like ’em plenty that way out there,

She has the love of ev’ry fella

She does a dance and when she starts By the river Nile,

The boys all take their old sweethearts And throw them to the crocodiles,

And ev’ry sheik in the audience jumps up and yells that she’s immense,

How they love EGYPTIAN ELLA.

All the other dancers from the desert to the Nile,

One by one admit that they are jealous

For altho’ they dance each night and wear their sweetest smile

Ella’s tent the one that draws the fellas

And yet her dance is something they can’t steal

For nothing else could do it but an eel:

CHORUS:

When the first sweet notes of the music sound

The boys all gather from miles around

Just to see EGYPTIAN ELLA;

And folks all know when those caravans

Start pouring in from the desert sands

That it must be EGYPTIAN ELLA;

Then Mister Sphinx sits up and blinks,

There’s so much to see,

She squirms and shakes so the worms and snakes

All bite themselves from jealousy,

She’s a great big gal in a great big land

and the boys all give her a great big hand,

How they love EGYPTIAN ELLA.

LAST CHORUS:

The boys hang around but she plainly states

She doesn’t care a fig about dates,

And they can’t make EGYPTIAN ELLA

A sheik tried to kidnap her once I’m told

But she shook so much that he lost his hold,

He couldn’t take EGYPTIAN ELLA.

So the Pasha wrote her a royal note

With his royal fist,

It said because of the dance she does,

She’s on his royal waiting list,

And that’s how fame of a diff’rent sort

has come at last from an indoor sport

To our own EGYPTIAN ELLA.

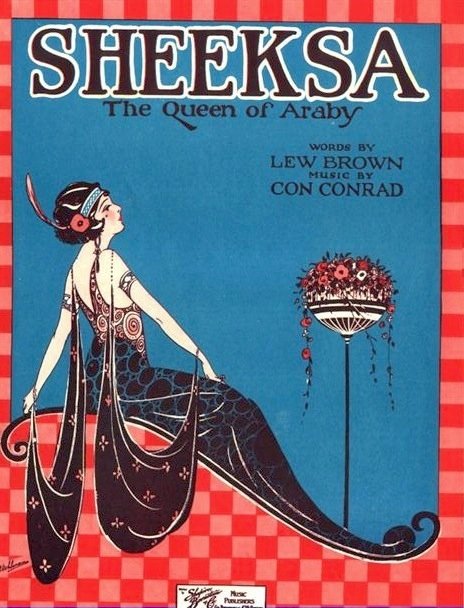

The Sheik Rage

In the wake of the popular rage unleashed by Rudolf Valentino’s film “The Sheik” and its sequels, many songs were written to compete with or capitalize on the Arab craze. “I’m Looking for the Sheik of Araby,” “The Sheik of Avenue B,” “Lovin’ Sam, the Sheik of Alabam’,” and “Sheeksa.”

Only in the Yiddish-speaking theatre was it possible to have this song about a woman who wants to find her sheik in the east. The whole purpose of the song seems to be a set-up for the punch line of the title: if a Jewish girl were to marry a sheik, she would, grammatically speaking, become a “Sheeksa,” construed as the feminine form of “sheik.” In this song, as the price of affection for her hero, the Jewish girl becomes assimilated into a gentile society, conveniently ignoring the fact that the Arab sheik is also a Semite. Also as we have seen in other songs, the geography and demography of the Middle East are hopelessly jumbled: the sheik of the Sahara lives in Turkey inhabited by Arabs.

SHEEKSA (THE QUEEN OF ARABY) (click here for details)

SHEEKSA (THE QUEEN OF ARABY) (click here for details)

w. Lew Brown; m. Con Conrad

©1923 Shapiro, Bernstein & Co., Inc., New York

Lovesick Sara once read about the Sheik

She asked someone upon the street last week

If the Sheik should marry me

Tell me what I’d be,

He said, “You’d be a SHEEKSA, the Queen of Araby”

She packed her grip and say

For Turkey sailed away

She met the Sheik, he pinched her cheek,

And married her next day:

CHORUS:

She wears nice clothes like Theda Bara

She says her nose is Roman

And they can’t see her face

But they all know it’s Roman

‘Cause it roams around the place

She dances for the Sheik ev’ry night

He tells her she’s his Turkish delight

She’s dressed in shredded wheat

And when they find it’s good to eat

They’ll fix her

The SHEEKSA, the Queen of Araby.

Lovesick Sara, she bought a barber chair

She made all of the Arabs bob their hair

Wrote her mother “Take all this hair I send to you

And start a mattress bus’ness

That’s what you ought to do”

I’ll send some ev’ry day

I know it ought to pay

If my friend Sam asks where I am

Just show him this and say:

Sara, the SHEEKSA of Sahara

She got to be a ho ly terror

They made her ride a camel

She said, “Don’t be a chump

A camel is a cripple

On his back he’s got a hump

She poses on those big Turkish rugs,

And on her head she balances jugs

They know she’s the Queen all-right

Because she crowned the Sheik last night

Some mixer,

The SHEEKSA, the Queen of Araby

The Jewish Girl Triumphs

Rebecca, as we have seen, modestly took some of the credit for toppling the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I. By the time her song was popular, the Empire had become the Turkish Republic and no longer posed a threat to the west. But the mythological Turk lived on in, for example, the comical figure of the Pasha (who survives in Walt Disney’s “Aladdin”) who could always be manipulated by others for their own purposes. The cultural misinformation continued nonetheless, when Sasha boasts of feeding the Pasha kosher meat; Muslims and Jews share a common prohibition on eating pork (cf. the second verse: ”No Mohammedan eats ham”). Also, Sasha becomes one of the sixty (or sixty-one) wives in the harem, another manifestation of the western erotic fantasy that Islam allows virtually unlimited wives (the Qur’an permits up to four). American moral sensitivities may also be active in this reference, as vaudeville was “family entertainment” and performers were warned about using strong language and telling “blue” stories. If Sasha wanted to remain under contract on the vaudeville circuits, she could not boast of her role as a concubine and so had to refer to her status as being married, albeit in a polygamous arrangement.

SASHA (THE PASSION OF THE PASHA)

w. William Rose, Ballard MacDonald; m. Jesse Greer

©1930 William Rose, Inc., New York

I was trav’ling through the Orient,

like a tourist strictly pleasure bent,

When a bunch of Arabs crept up from the rear.

And a guy named Achmed Hammel,

Went and knocked me off my Camel,

Without as much as “Pardon me, my dear.”

He sold me to the Sultan

like a guy would sell a cow,

The Harem dames all call me names

for I’m his favorite now.

CHORUS:

I’m Sasha, the Passion of the Pasha,

Most of his time is spent

Hanging around my tent.

The Pasha, he claps his hands for Sasha,

And when we bill and coo,

It’s poo-poo-poo-poo-pa-roo-poo.

Since I cooked for him a dinner

he’s been terribly sweet,

And oh how appreciates a little Kosher meat;

And speakin’ about the art of sheikin’

Oh the Sultans’s wife is a wonderful life,

Providing you don’t weaken.

Ev’rything is so peculiar there,

you’ll get mixed up and they’ll fool you there,

For example no Mohammedan eats ham,

As for me I find it dandy there,

Ev’rything is nuts and candy there,

You should see me eat a plate of Persian lamb.

And from my harem window

I’m admired by all the males,

But you can’t tell the difference

When I’m wearing seven veils.

I’m Sasha, the Passion of the Pasha,

Tho he’s an old Shlemiel

Still he’s got sex appeal,

The Pasha, he claps his hands for Sasha.

Then I know right away

The Pasha is crazy to play.

In his palace he’s got Alice,

he’s got Rose and Marie,

And fifty-seven others

but he concentrates on me;

No wonder I’ve gone to rack and ruin,

Neath the shelt’ring palms

In the Sultan’s arms,

do I know what I’m doin’?

Sasha has become the latter-day Queen Esther, the Jewish maiden who has bedazzled the ruler of the empire by becoming the star performer of the harem. She lives a fantasy of the modern Jewish princess, traveling, apparently on her own, through the Orient on a camel when a group of Arabs kidnap her and sell her into slavery to the Pasha, where her domestic and inter-personal skills immediately endear her to her new owner. “Oh the sultan’s wife is a wonderful life, providing you don’t weaken.”

Sasha has come a long way from the days of Sadie, Rebecca, Sophie and the rest of those Jewish working girls. The three decades separating these women saw great changes in the welfare and prospects for all immigrant women, not only in the workforce but also in the professions that had opened to them in the intervening years. The riches and opulence of the Orient were no longer restricted to dreams focused on one part of the globe; new and greater real wealth could be found in one’s own backyard, in a booming American economy poised to implode.

ENDNOTES

[i] From History of Passaic and Its Environs (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Co., 1923?) vol. 1, p.495.

In this context, “Dutch” probably does mean Dutch ( i.e., “Hollander” as my German grandfather would say) and is not to taken as an Americanized version of “deutsch.”

“[I]n the galleries men and women left their seats to stand so they might look down on the prima donna [Olive Fremstad] as she kissed the dead lips of the head of John the Baptist. Then they sank back in their chairs and shuddered.” New York Times, Jan. 23, 1907, p. 9.

There were a number of songs for men , but there were invariably in the mode of “if I were in charge of the harem” and depended on male fantasies rather then actual descriptions of activities inside the harem, e.g., “In My Harem” by Irving Berlin and “Give Me The Sultan’s Harem” by Alex Gerber and Abner Silver.

The song appears with both titles and to further muddle the stereotypes, one edition has a photo of Eddie Cantor in blackface performing the song in “The Midnight Rounders” (1920).

Moussa Schinasi, a Turkish immigrant, patented a cigarette rolling machine and sold cigarettes under his name brand. Mogul, Murad and Egyptian Deities were other brands of the day, all manufactured by the P. Lorillard corporation. In the music, this line is to be chanted in the Middle Eastern style.

It is not uncommon in these songs to have Indian references mixed in with Middle Eastern themes: e.g., mosques have “temple bells” to call the faithful to prayer.

As in many other songs, the geography is hopelessly confused, with Araby in Turkey and the Sheik in Araby/Sahara.

Like Lena in Palesteena, her dress fashion is ridiculous except as an indication of its insubstantial nature.

The mention of the barber chair is an example of cultural interchange: Sara will introduce the latest American rage for women to wear bobbed hair to the Arabs and bring them into the modern world while affording her family back in America a living stuffing mattresses with all the shorn hair she will send back.