This article describes some of the songs dealing with the Middle East that were sung on the vaudeville stages of America in the first part of the 20th century. Between 1900 and 1935 the number of popular songs composed on topics pertaining to the Middle East far exceeded those of any other time period in American history until the Persian Gulf War.

Between 1905 and 1908 the Salome craze, prompted by the premiere of Richard Strauss’ opera, flooded Coney Island and vaudeville theaters with numerous parodies and take-offs (pun intended). This was followed by a spate of songs about the ever-popular Cleopatra. But several other factors, both economic and social, prompted a sustained popular interest in things and people “oriental.” The importing of Turkish tobacco prompted cigarette brand names such as Fatimas, Murads, Egyptian Deities and Rameses. Literary groups were memorizing Fitzgerald’s translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. Eventually, all would be caught up in the conflagration of World War I in which Turkey joined with the Central Powers against the Allies.

At the turn of the 20th century vaudeville was featured exclusively in almost two thousand theaters across the country and was primarily family entertainment. Performers were reminded by their booking agents to “keep it clean.” A sign posted backstage at a theater in Florida was typical of the mood:

PERFORMERS TAKE NOTICE

We are playing to ladies and children and you will do the Management a favor

by cutting out any double entenders, the word damrotten or anything suggestive.

The vaudeville bill was a balance among seven or eight acts, or “turns,” known by such terms as “knockabout act,” a “protean act” (quick-change artist) or an “alley oop” (tumbling, balancing, weight-lifting, etc.). Some were dumb acts that required no speaking, very popular in circumstances where the audience might not speak a common language; others were monologues that recounted adventures like “Casey at the Bat” or a wedding gone awry, be it Irish, German, or Jewish. There were skits of all sorts, “Doctor Krankheit” and “Who’s On First?” being two that have entered that Vaudeville Valhalla of immortals.

And then there were the songs. Some songs would be identified with specific performers like Blanche Ring singing “Rings on My Fingers, Bells on My Toes” or Al Jolson doing “Sunny Boy.” For untold numbers of songs, however, the performer played the role of the DJ today: he or she was a song plugger for the publishing houses of Tin Pan Alley. Songs were introduced into acts with no connection to the program except that the performer had been paid by the publisher to plug the song. Sometimes a song would recur four or five times in the same program, done by different actors. Part of the pay-off can be seen in the cover layouts of the printed sheet music: various editions of a song featured photos of the different performers who plugged the song in their acts.

The songs themselves became standardized into a 32-bar chorus with an AABA pattern for the music: the opening statement was repeated once, followed by a “bridge” section, and the final reprise of the opening. Like the sonnet form in literature this pattern constrained the composer and lyricist to evoke all their creativity to tell a story in several verses and the repeated chorus. As Stephen Sondheim recently remarked, “It’s about economy.” You had only so many (so few!) minutes on stage and an even shorter time to catch the audience’s attention and hold it. Variety acts were honed to perfection in town after town, then run for years on the circuits.

The lyrics were an art form of their own. The verses would tell stories that resonated with the audience. There were tales of adventuresome men discovering gorgeous women of the East. There were the vamps and sirens luring men to delightful and terrible fates. For backgrounds there was a group of stock images, among them the sultan’s palace, a tent in a desert oasis, the pyramids and the Nile River.

An appreciation of this “economy” can be demonstrated by comparing two songs with the same title, a hypothetical one from the 50s, one from 1917. They are both called “Cleopatra.” The lyrics to the version from the 50s could be summarized very quickly: “Oh Cleo, Cleo, Cleopatra, Yeah, Yeah.” (You had to be there!) The vaudeville version played in theaters with audiences that represented the ethnic mix of the cities: the Irish, the African-Americans, the Italians, the Germans (=”Dutch”) and the “Germans” (=Jews). Vaudeville was an equal opportunity stereotyper; it depended on instantly recognizable cues to gain the attention of the audience, cues that today may sound offensive. At the time, however, Will Rogers best expressed what vaudeville comedy was all about: “Everything is funny as long as it is happening to somebody else.”

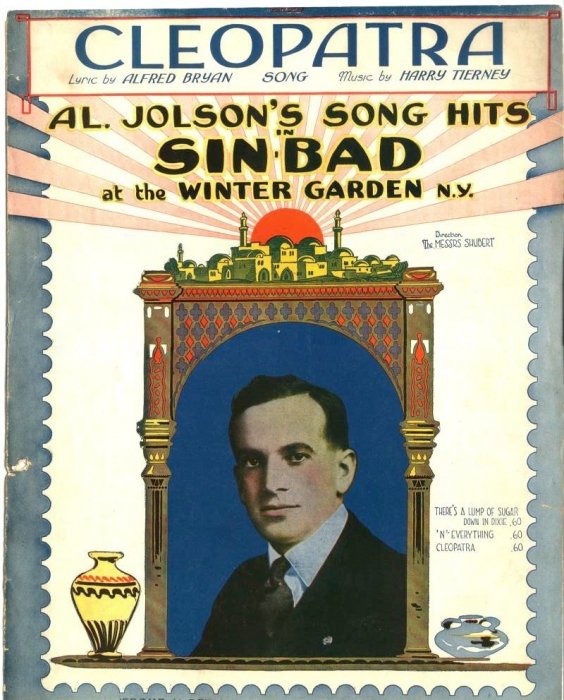

The vaudeville song was featured in two different shows, “What Next?” and “Sinbad,” both starring Al Jolson. To gain the maximum advantage for the star, the writers of this “Cleopatra” actually included in the chorus a “plug” for another Jolson hit from a different show, “Yaaka Hula Hickey Dula.” The mention of a “Hawaiian Love Song” in a number about Cleopatra may sound far-fetched, but there is an ingenious explanation, as you will hear.

For the lyricists of the day, “oriental” was shorthand for designating anything “east of Suez,” or more properly, anything east of Morocco or the Dardanelles. There was no concern for precise geography or national boundaries. Mecca could be in Turkey, Baghdad in Persia, and a Salome dancer named “Princess Oy-Vay-is-meer” could be called a “Hindoo lady.”

The music for these songs was also constrained by the form. The story had to come through with the proper stresses in phrasing. The atmosphere of the song was frequently established by short, 2-measure phrases freely borrowed from the repertoire of the light classics. In the case of “oriental” songs, the vocabulary began with the minor key, to which were added “hollow fifths,” tom-tom rhythms in the base and snatches of themes from César Cui’s “Orientale,” Albert Ketelbey’s “In a Persian Market,” or best known of all, the “hootchy-kootchy” theme of uncertain origin that opens Irving Berlin’s “In My Harem.”

Listen as it all comes together with Alfred Bryan’s lyric and Harry Teirney’s music.

CLEOPATRA (click here for details)

Music by Harry Tierney; words by Alfred Bryan; ©1917 Jerome H. Remick & Co.

You’ve heard of Cleopatra who lived down beside the Nile,

She made a “Mark” of Anthony and won him with her smile.

They say she was Egyptian, but I’ve reason to construe

She was Jewish and Hawaiian with a dash of Irish, too.

CHORUS:

When she stroll’d with bold Mark Anthony on Egypt’s yellow sands,

You could see that she was Jewish by the motion of her hands.

She would shake her hands and shoulders off,

That’s the way she made her “muscle tough”–

I think she was Hawaiian from Honolulu too,

She would dance like this to the Yaka hoola, hicky doo-la, Yaka hoola, hicky doo.

Her mother’s name was Cleo and her father’s name was Pat,

So they called her Cleopatra, Now what do you think of that?

She had a thousand lovers in the true Egyptian style,

When she grew sick of one she threw him to the crocodile.

They say she died heart-broken after many sad regrets,

I really think she died from smoking Milo Cigarettes.

As early as 1907 ethnic vaudeville acts were in trouble. Society and the audiences were changing as the immigrant generation passed into the assimilated generation. The Russell Brothers had a female impersonation routine called “The Irish Servant Girls” that they had played for years. Then the Ancient Order of Hibernians and the United Irish Societies of New York decided that the act was too broad a caricature of the Irish in general and of fair colleens in particular. At one performance the routine was interrupted by raucous outbursts, leading to the arrest (by Irish policemen) of some 40 Irishmen on charges of disturbing the peace. When the case came to trial before magistrates Keary and Fleming, both Irish, the manager of the theatre was willing to swear that he saw things flying through the air. He was certain that he saw Joe Harrington throw something, but when it came down to brass tacks he had to admit that the thing Harrington threw might have been a bouquet.

In his ruling the judge declared,

My impression of the Russell’s show…is very bad. The public should not encourage or patronize such acts. No man of blood, particularly of Irish blood, could sit and listen to anyone who would thus disgrace the women of his race. I am satisfied from the testimony that this act was indecent, shocking, and vulgar.

The Russell Brothers took to the road for a while, but were no longer in the big time and, by 1913, they were out of variety.

A similar fate would overtake the Jewish comics within the decade. This time the action started with the Chicago Anti-Stage Jew Ridicule Committee headed by Miss Nellie Eda Osherman. Within five months the Committee had made its point and the management of the Majestic Theatre announced:

Unless they promise to be very circumspect in word, deed and make-up, all comic roustabouts whose stock in trade is gibes at the Jewish race will part company with the management of the Majestic Theatre at the expiration of their present contracts.

In the words of one vaudevillian, Sam Bernard, first the Irish, and now the Jewish comedian was gefutch [finished].

The stage German was an early casualty of the outbreak of World War I in 1914. In Britain German acts were banned, precipitating a migration of these acts to still-neutral America. Some of the German acts became “Swiss” on the voyage across the Atlantic, but the befuddled and loveable stage German was being pushed off by the tabloid images of the despicable Hun committing atrocities in Belgium.

For the comics in vaudeville, new material and new approaches were needed. One solution was to shift from situational jokes embedded in skits to one-liners and wise cracks, “zingers” that did not depend on any ethnic connection. “Take my wife, please!”

Another solution was to find a new target for the humor. If Europeans, eastern and western, were no longer fair game, then the search had to be widened to non-European peoples. The very war which provoked the ban of “Dutch” comedians presented a new-old villain, the Turk. Americans as such had no collective memory of the Ottoman armies at the gates of Vienna, but they quickly learned about the Central Powers and the Berlin-Istanbul axis. American ties with Turkey went back to the early 19th century when trade relations were established after the Barbary Wars. Christian missionaries in Turkey and the Levant relayed information about Turkish society back to congregations in America, while immigration to America from Syria and Lebanon, lands under Ottoman rule, added to the audiences’ awareness of the Eastern Mediterranean.

From the standpoint of “orientalism” Turkey, and in particular Istanbul, offered all the necessary ingredients for an exotic spectacle: the sultan’s magnificent palace, the harem, and, of course, beautiful women in scanty clothing lounging about in Turkish baths, scenes known so well from “oriental” paintings by European artists. Add to this mix the stories of the Arabian Nights (published in different versions for children and adults) and various tourist accounts of life in the East and there was a sufficient supply of stereotypes to carry “orientalism” through the war and long after.

It’s time to take a trip to the east, or at least to the east as seen through the eyes of the songwriters and lyricists of vaudeville.

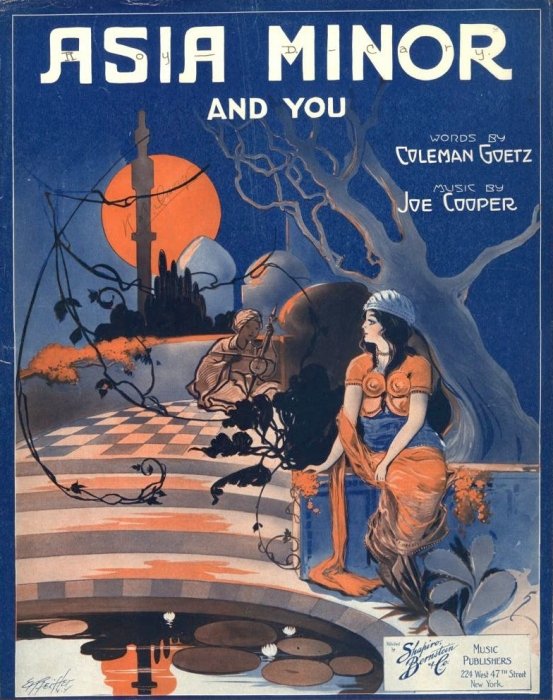

We begin by sailing across the sea to those exotic lands, a trip prompted by our western hero’s search for his love, Nona (in the words of W. C. Fields, “such a euphonious appellation”), whom he met by “a quaint old pagoda” in Asia Minor.

ASIA MINOR AND YOU (click here for details)

ASIA MINOR AND YOU (click here for details)

Music by Joe Cooper; words by Coleman Goetz; ©1916 Shapiro, Bernstein, & Co.

Asia’s a wonderful land of love,

Bless’d by the Heavens so fair,

I met a wonderful girl I love,

That’s why I’m going there,

Picture a quaint old pagoda of pine,

That’s just the place where we met,

I’m going back again to make her mine,

Somehow I can’t forget:

CHORUS:

So I’m goin’ to take a liner,

To Asia Minor,

That’s where I’m sure I’ll find her,

She shows

By the way that she looks she knows

That she and I will be so content

In the Orient Where I met her,

Nona, soon we will own a

Home that is built for two,

(And that is true),

Words express my feeling so mild,

Like a mother sighs for a child,

I sigh for Asia Minor and you.

Nona makes life like an old sweet song,

Tho’ I’ve met girls by the score,

I seem to hear her the whole night long,

Call from that foreign shore,

“Soon you said you’d be returning to me,

Do as you said, I implore!”

I’m goin’ to send a message from my heart,

Not only that but more.

For the woman who travelled to the orient, the results can be quite different. Eddie Cantor featured this song that recounted what happened when “Rebecca Came Back from Mecca.” Not only does Rebecca get “orientalized,” but, if the song is to be believed, a nice Jewish girl from New York contributed to the downfall of the commander-in-chief of the Ottoman Empire.

REBECCA CAME BACK FROM MECCA (click here for details)

REBECCA CAME BACK FROM MECCA (click here for details)

Words and music by Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby; ©1921 Waterson, Berlin and Snyder Co.

Across the way from where I live, There lives a girl and her name is Rebecca,

She’s twenty-three.

She saw an oriental show And then decided she would go To Mecca,

across the sea.

And so she went one day, To Turkey far away,

And she lived near the Sultan’s den;

She stayed there just two years, Got full of new ideas,

And now she’s back home again.

CHORUS:

Since Rebecca came back from Mecca,

All day long she keeps on smoking Turkish tobecca;

With her veil upon her face,

She keeps dancing ’round the place,

And yesterday her father found her

With a Turkish towel around her,

Oh! Oh! Ev’ryone’s worried so;

They think she’s crazy in the dome;

She’s as bold as Theda Bara,

Theda’s bare but Becky’s barer.

Since Rebecca came back home

In Mecca where the nights are hot, Rebecca got and awful lot of learning,

She certainly did.

She goes to sleep when shadows creep And has to keep a bowl of incense burning,

Some classy kid!

Her mother feels so sad, Her brother Moe is mad, And he keeps on complaining so,

To satisfy her whim, she keeps on calling him “Mohammed” instead of Moe.

CHORUS:

Since Rebecca came back from Mecca,

All day long she keeps on smoking Turkish tobecca.

She lays on a Turkish rug,

Ev’ryone says she’s a bug,

And since she’s back home from the Harem,

She has clothes but she don’t wear ’em.

Oh! Oh! Ev’ryone’s worried so;

She made the Sultan lose his throne;

Once her little sister Sonia

Wore her clothes and got pneumonia,

Since Rebecca came back home.

Although the ethnic comics had been pushed from the stage, there was still room to combine the old acts with the new orientalism. In the next instance, the point of the song depends on a “double entender” concerning the meaning of the word “Turk.” The Oxford English Dictionary notes that the word is “applied to anyone having qualities attributed to the Turks; a cruel, rigorous, or tyrannical man; any one behaving as a barbarian or savage; one who treats his wife hardly [harshly]; a bad-tempered or unmanageable man;” in other words, an Irishman.

MY TURKISH OPAL (FROM CONSTANTINOPLE) (click here for details)

MY TURKISH OPAL (FROM CONSTANTINOPLE) (click here for details)

Music by Edna Williams; words by Arthur Gillespie; ©1912 Joseph W. Stern & Co.

An Irish Turk named Pat McGuirk was sent to the Turkish war,

So off he went with his regiment upon a Turkish shore.

They called upon the Sultan, but the Sultan turned them down,

So they captured all the harems in Constantinople town.

A girl whose name was Opal danced her way into Pat’s heart.

Said he, “I’d like to steal you and then from this land depart–

CHORUS:

Be my little Turkish Opal from Constantinople,

I’ll be your little Irish Em’rald, and we’ll have a wedding grand.

I’ll build a little hut in clover with shamrocks all over,

You’ll be Missus McGuirk and a regular Turk in Ireland.”

Pat came back on a camel’s back with saddle built for two,

Said He, “A Turk who is named McGuirk in Ireland’s nothing new!”

They interviewed the Sultan and she begged for her release,

But he chased them and their camel out of Turkey into Greece.

They’re living now in Ireland just outside the town of Cork

And last Thanksgiving Pat brought home a Turkey and a Stork.

When it comes to the women of the east, the lyricists differed in their assessments of their beauty and its effect on the western men who were always the explicit or implicit lovers. At times, however, even the eastern women turned out to be something other than what they seemed, as in the case of Milo. A quick explanation to the references in the verses: Eva Tanguay, called by the publicists of the day by such titles as “Mother Eve’s Merriest Daughter,” “The Human Gyroscope,” and “Eva [who] Put the Tang in Tanguay,” was a vaudeville sensation with her signature song “I Don’t Care,” published the same year as “Milo.” The operetta “Florodora” had been the hit comedy several years earlier with its famous musical question, “Pray tell me, pretty maiden, are there any more at home like you?”

MILO (click here for details)

Music by Alfred Solman and Benj. H. Burt; words by Benj. H. Burt; ©1905 Joseph Stern & Co.

I met a girl named Milo, I knew at Coney Isle-o,

When I was out in Turkey looking for work;

I met her in the Harem dancing the “don’t you care-em,”

She made a fascinating Yankee Doodle Turk.

She was the leading dancer, so now you see the “answer,”

I wanted Milo, she wanted me:

But when I asked the Sultan, while we were out at luncheon,

My proposition he couldn’t see;

So ev’ry night, when he slept tight, In his backyard I would sing: Oh!

CHORUS:

Milo, You’re just my style-o,

I’ll take my hat off to you,

You’ve got me guessing, it’s true,

I’ve a feeling for you,

My Milo, say yes! and smile-o!

We’ll live in style-o, My Milo,

All life through.

She told me she had landed when “Florodora” stranded,

She’d been a “pretty maiden” once one a time;

I found when we had spoken, her home was in Hoboken,

She knew my parents and a lot of friends of mine.

I told her that her mother, her sister, Aunt and brother,

All could stop working and live on me;

So while his “Nobs” [“Nibs”?] was sleeping,

From Turkey we were sneaking,

To Coney Isle-o, down by the Sea.

A boat we took, to Sandy Hook, and the band began to play: Oh!

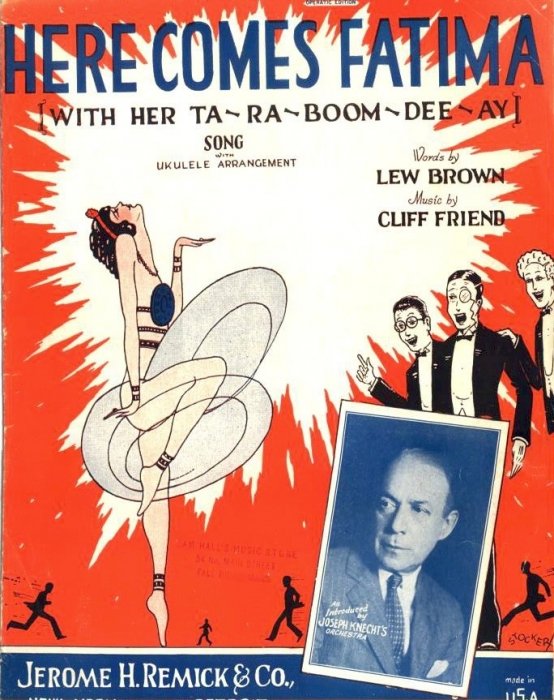

Another type of woman was the vamp, typified by Theda Bara in the movies (and copied by Rebecca, whom we have already met). Instead of being the romantic object of desire, the vamp was the siren, luring men to their destruction. While the parties lasted, these ladies were always exciting, even during Prohibition when bath-tub gin was distributed in White Rock soda bottles. To update this idea, one must think Nicole or Dolly, although the physical attributes are quite different, as you will hear.

HERE COMES FATIMA (click here for details)

HERE COMES FATIMA (click here for details)

Music by Cliff Friend; words by Lew Brown; ©1926 Jerome H. Remick & Co.

From a Turkish harem came Fatima

With a pair of eyes that the boys all idolize,

All the girls said she was quite a schemer,

She would always go for the other girlie’s beau.

She loved to go to parties, they tried to keep her out,

And every time they saw her coming they’d begin to shout

CHORUS:

Keep the fellows quiet (sh!) Tell them not to play

‘Cause here comes Fatima with her ta-ra-boom-dee-ay.

Go and hide the “White Rock,” Put the food away,

‘Cause here comes Fatima and she spoils a perfect day.

Out the window we must go, if she comes in we’re through,

‘Cause you don’t know just what her ta-ra-boom-dee-ay can do,

Get a big policeman, Keep him here all day,

‘Cause here comes Fatima with her ta-ra-boom-dee-ay.

Back to Turkish harem went Fatima

But the Turks said “No, we would rather have you go;

You broke up too many homes, Fatima,

Had some good men shot and goodness knows what not.”

So she got on a steamer and went to gay Paree,

The Frenchmen saw her coming and they hollered out “wee-wee.”

CHORUS:

Lock the doors and windows, Say we’re out today,

‘Cause here comes Fatima with her ta-ra-boom-dee-ay.

Ev’rybody’s nervous, Call up Doctor Gray,

Here comes Fatima and Fatima loves to play.

Out the window we must go if she plays “hide and seek;”

I guarantee that you wouldn’t see your fellow for a week.

Break up all the dishes, She’ll break them anyway,

Here comes Fatima with her ta-ra-boom-dee-ay.

Put John in the cellar, Lock up Bill and Ray,

‘Cause here comes Fatima with her ta-ra-boom-dee-ay.

Tie Sam in the woodshed, He don’t look O.K.,

If he sees Fatima he’ll postpone our wedding day.

When she starts to dance around, Oh boy, how she allures,

She’s got a shape that comes straight down, but oh how it detours,

Turn out all the bloodhounds, Keep that vamp away,

‘Cause here comes Fatima with her ta-ra-boom-dee-ay.

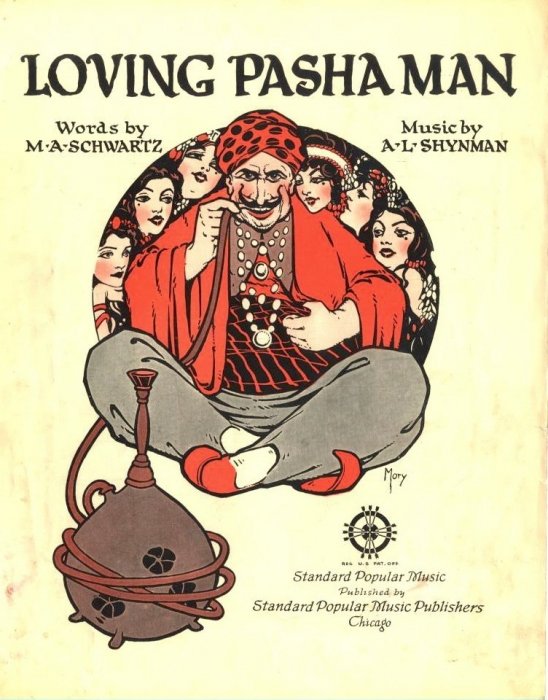

In general the male inhabitants of the orient do not fare well in any of these songs. One notable exception is the “Sheik of Araby,” but in the novel that gave rise to the song and film the sheik turns out to be the son of an English nobleman and an impoverished, but noble, Spanish mother, hence he is safely European. As a rule eastern men are seen as foolish, easily duped, and indolent. Viewed by the “new woman” emerging in the 1920s and seeking status in a male-dominated world, the model of the Sheik, Sultan, or Pasha, merely confirmed her assertion, “All men are Turks at heart.” Men wanted many female partners conveniently confined in a harem and minimally clothed. Under these circumstances, it was surprising to hear this favorable report of a “Loving Pasha Man,” even if the lyrics locate a Turkish Pasha in Persia and the words “gay” and “queer” have changed their meanings for us.

LOVING PASHA MAN (click here for details)

LOVING PASHA MAN (click here for details)

Music by A. L. Shynman, words by M. A. Schwartz; ©1913, Standard Popular Music Publishers

Where the harem is the custom, Where a man has wives galore,

And he loves each wife, More than all his life, Maybe more.

Where the ladies veil their faces, So their eyes alone appear;

Wifies short or tall, Pasha loves them all, For he’s a dear.

CHORUS:

Oh my Pasha, Pasha man,

(Loving man, in his clan, he’s a man)

Loves me like no other can,

(Oh he can, yes he can, always can,)

Oriental rugs and hugs, oh life’s so gay,

In the harem where I always want to stay.

He’s queer, But he’s a dear,

never fear, when he’s near, he’s a dear.

While a dervish whirls and whirls,

(how he whirls, how he swirls, how he twirls,)

Pasha kisses all his girls,

(lovely girls, gives them pearls, precious pearls,)

While we dance all day,

In that Persian way,

For that loving Pasha Man.

Pasha calls the roll each morning

Wifies all must answer, “Here,”

“I love only you, Promise to be true to you, dear.”

Ev’ry thing is bliss in Persia,

Land of love and harmony;

Pasha says, “My dear, Eighty-four come here,

A kiss for thee.”

With the Armistice in 1918 the Great Powers began the complicated business of parcelling out the territories of the defeated empires. In the vaudeville houses the political and diplomatic issues were kept very simple for the masses. The nations of Europe could argue for this or that piece of the Ottoman Empire, but as far as our hero was concerned, he was prepared to offer a unique solution to one very important part of the problem.

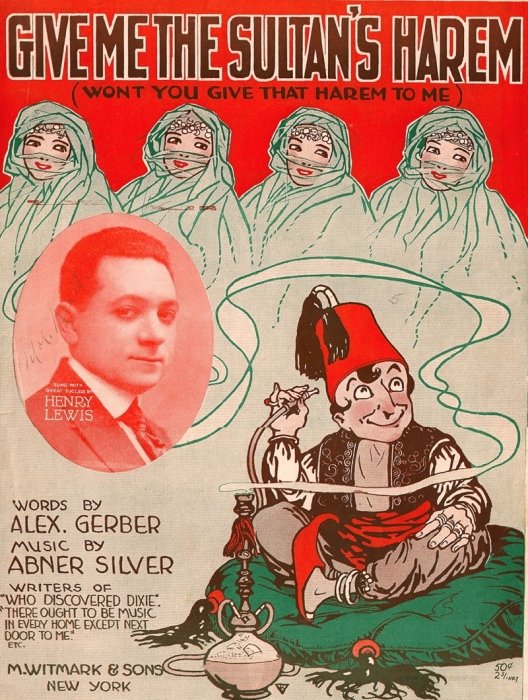

GIVE ME THE SULTAN’S HAREM (click here for details)

GIVE ME THE SULTAN’S HAREM (click here for details)

Music by Abner Silver, words by Alex Gerber; ©1919 M. Witmark & Co.

I dreamed that I was at the Peace Conference,

Where England and France and Italy

Each got her share of her indemnity.

And after they divided up the dish,

They asked me if there’s anything that I’d wish.

I was so shy, I thought they’d die,

When I made this reply:

CHORUS:

Give me the Harem, the old Sultan’s Harem,

That’s the only thing I crave.

The Sultan’s too old, for he’s past eighty-three,

And his thousand wives need a fellow like me.

I’ll never beat them, with kindness I’ll treat them,

And all the I ask is a trial;

Imagine me sitting on a carpeted floor,

Telling my slave to bring me wife “Ninety Four.”

I’ll be so gallant, I’m chucked full of talent,

Won’t you give that Harem to me?

The diplomats all listened to my plea,

They wondered just what was the matter with me,

But I kept on asking for a trial,

I tried to show them it was worth the while.

Just then they asked if I was qualified,

And I replied, “You folks will be satisfied,

I’ll prove to you, that I’ll be true,

But here’s what you must do:”

CHORUS:

Give me the Harem, the old Sultan’s Harem,

That’s the only thing I crave,

I’ll take off the veils that they wear on their face,

The young ones I’ll keep and the old ones I’ll chase.

I’ll give them freedom, on garlic I’ll feed ’em,

So they can grown stronger for me,

King Solomon was four hundred years when he died,

If I live till forty three I’ll be satisfied,

I’ll be a wizard, a real Harem lizard,

Won’t you give the Harem to me?

The legacy of vaudeville orientalism is a set of stereotypes that have survived the transition from the local theaters and variety halls to the silver screen and television. The oriental scenes of bustling urban splendor contrasted with barren desert empiness are enshrined in the Hollywood sets of opulent palaces in “The Thief of Bagdad” and the vast stretches of the Wadi Rum captured in all its wide-screen glory in “Lawrence of Arabia.”

In dealing with people, the women are mostly seen as under-dressed as the medium will allow: in paintings and prints, the women of the Turkish bath are shown nude; in films and on stage they wear as little as the local censor will permit. The men are, by and large, unsavory, corrupted by barbaric ways or ill-gotten wealth; in earlier productions this was plunder, more recently it has been oil, drugs and extortion by acts of terrorism.

Stereotyping reveals itself in the depersonalization of people; they are not really human (like you and I), hence they cannot be expected to behave as we do. One indicator of this for the vaudeville oriental is the fact that only the women have proper given names: Fatima, Cleopatra, Milo, Nona, etc. The men are known almost exclusively by titles: the sheik, the pasha, the sultan, etc. One exception might be Omar Khayyam, but his reputation comes not from any stage tradition, but from literature and the popularity of Edward Fitzgerald’s translation of the Rubaiyat. When the male leads require something more than a title in the dramatis personae, they typically are designated with parody names, not authentic Arabic or Turkish names. In the oriental operettas at the end of the 19th century, for example, the lead of “Tabasco” (1894), set in Tangier, was “Hot-Ham-Head Pasha”; in “The Ameer” (1899) his name was “Iffe Khan.” A personal favorite comes from the remake of the story of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves as “An Arabian Girl and the Forty Thieves.” This modernized version of the tale from 1899 is set in Chicago[!] where the forty thieves are in league with the corrupt chief of police, whose name is “Arrab y Gorrah.”

The perserverance of these mostly negative stereotypes of the places and people of the Middle East still influences the way we react to contemporary events in the region. As Walter Lippmann noted seventy years ago:”stereotypes are the store of information we carry about in our heads to fill in the rest of the picture provoked by partial information or sensation.” It is a matter of conserving valuable “disk space” in our brains that “we have a repertory of stereotypes to draw on–preconceptions about the world around us.” While this is an economical storage mechanism for our brains, it carries with it the danger that “our stereotypical world is not necessarily the world we should like it to be. It is simply the kind of world we expect it to be.” (emphasis added)

The legacy of orientalism stereotypes in America vaudeville continues in our cartoons, films and television. A few years ago a cartoonist for the Washington Post presented “False Starts,” a send-up of cartoon strips that didn’t pass editorial muster. One of them was entitled “Mullah Knows Best.” The two panels show an Iranian woman wearing a black chadoor asking her husband, “Does this make me look fatwah?” In the second panel he gallantly replies, “Nonsense, you look chadorable.”

The Walt Disney Company had a box-office success in the cartoon feature “Aladdin, but the film aroused negative reactions from some groups because of the hidden and overt messages contained in the lyrics. The American Life League of Stafford, Virginia, discovered an audible message buried in the soundtrack that exorts, “Good teen-agers, take off your clothes.” The idea that people in the Middle East don’t wear clothes persists.

A more serious issue was the lyric in the opening song, which prompted an editorial in the New York Times under the heading “It’s Racist, But Hey, It’s Disney.” The original lyric read:

Oh, I come from a land, From a faraway place, Where the caravan camels roam.

Where they cut off your ear, If they don’t like your face, It’s barabaric, but hey, it’s home.

After pressure was brought to bear on the company by the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, two lines were changed. Instead of cutting off an ear, a geography lesson was inserted: “Where it’s flat and immense, And the heat is intense…” but the last line remained unchanged: “home” is still barbaric. Stereotypes are hard to change, but as the Times editorial concluded, “To characterize an entire region with this sort of tongue-in-cheek bigotry, especially in a movie aimed at children, borders on barbaric.”

The challenge of this sort of orientalism is for us to recognize the preconceptions that were built into the original works, to see how contemporary events shaped western perceptions of the Middle East and still do. The negative stereotypes are so much a part of our mental baggage that we scarcely realize how easily we rely on them to interpret current events. There is a kind of cloning that goes on with these stereotypes in which successive generations of stage productions and films revert to earlier stage and film conventions rather than turning to readily available reality. For example, the “Salome Craze” of a century ago has reappeared in an unending succession of “belly dancers” introduced into films and stage shows for no other reason than to add some “spice” to the production. Even such a metaphor reveals the durability of these stereotypes: the orient always was the source of spices to enrich bland European dishes.

In their version of Orientalism, the vaudevillians’ “noble dreams” were limited to finding a lovely lady of the east to bring home to a life of domestic bliss in a bungalow somewhere in the country. The “wicked pleasures” were so much more fun and made for a better act, as you have heard. So as you enjoy the exhibition of “Orientalism in America,” and there is so much to enjoy, resist the temptation to accept the artist’s vision as reality. The antidote to these stereotypes remains meeting the people of the Middle East themselves in all their infinite variety, and not be misled by the paintings and songs that start by amusing and entertaining us in a straightforward fashion, but then, like Fatima, “Oh, how it detours!”

The social conditions of a century ago have changed. As Anthony Slide says in his introduction to the vaudeville that was:

What once passed for entertainment is now considered racist or politically incorrect. Adolf Hitler and the rise of Nazism in Germany put an end to the style of Jewish humor presented by Willie and Eugene Howard, Benny Rubin, and Ben Welch. The blackface antics of Aunt Jemima, Al Jolson, and Moran and Mack have no place in America of the 1990s. The anecdotes of Walter Kelly as the Virginia Judge would no longer find an audience, even in the Southern states.

Can we still laugh at these songs and enjoy the comedy in the spirit of an Eddie Cantor performing “When Rebecca Came Back From Mecca” in blackface on Broadway? One thing is certain: our parents and grandparents couldn’t wait to get to the vaudeville theater and laugh at the variety acts, the skits and the knockabout comedians. Vaudeville afforded a multicultural experience that was uniquely American in its breadth and diversity, where the goal of the performers was to play the Palace, and if you had the talent, you could make it on Broadway. Eddie Foy once said, “It may only be a street to most people, but to some of us it is a religion.”

Encore!

Here is a song that without fear or favor, without good sense or good taste, lampoons male and female, Turk and Arab, Jew and Egyptian, Persian and Pakistani. The range of its targets is matched only by the inaccuracy of its information.

TURKISH DELIGHT (click here for details)

TURKISH DELIGHT (click here for details)

Music by Ray Noble, words by Max Kester

©1937 Cinephonic Music Co., Ltd.; ©1948 Campbell-Connelly, Inc.

Once there was a Caliph and he lived in old Baghdad,

He led a most unhappy life, Be-Gum, Be-Gosh, Be-Gad;

He couldn’t sleep a wink at night, he had two hundred wives

Who had to tell him stories otherwise they lost their lives.

CHORUS:

Yah-ah-ah-ah, So the [first/next] wife told her tale.

Once there was a tourist who took a trip to Turkey,

He went out for adventure when the night was dark and murky,

He tried to kiss a Turkish girl, but she remarked, “My word,

You may be fond of Turkey, but I’m not that kind of bird.”

Sinbad was a sailor, and you know what sailors are!

He sailed about the seven seas, but once he went too far.

He saw a lovely mermaid a-combing out her locks,

The naked truth upset him and he soon was on the rocks.

King Solomon, that wise old man, he had a thousand wives,

He bought a lovely tourist bus [charabanc] to take them all for drives,

The tourist bus broke down one night and here’s where trouble starts,

His wives were waiting in a row and he’d got no spare parts.

The Oriental beauties, they veil their pretty faces,

Although they aren’t so careful about some other places,

They make whoopee and aren’t found out and here’s the reason why,

A woman in a veil can never tell a bare-faced lie.

Once there was a Caliph who went up a winding path,

And all at once he came upon the ladies’ Turkish bath;

The girls all screamed with horror at this masculine intrusion,

But it was quite all right for they were covered with confusion.

Cleopatra was a gal who always got her man,

She wooed a certain Emir who lived in Pakistan.

She wore her most exotic gown, she thought it would convince,

It did all right–He put it on, she hasn’t seen him since.

The Sultan of Morocco has a wonderful hareem,

With wives of every colour from chocolate to cream.

He’s only got three-sixty-five and yet it makes him groan,

For every time leap year comes round he has to sleep alone.

CHORUS:

Yah-ah-ah-ah, So the last wife told her tale.

ENDNOTES

.Frank Rich, “Conversations with Sondheim.” New York Times Magazine, March 12, 2000, p.38 ff., see p. 88.

.She appears in “Becky [Bifkowitz] from Babylon [Long Island, NY]” by Jean Schwartz and Abner Silver ©1921 Jerome H. Remick & Co., at the same time “Rebecca Came Back from Mecca” was issued.